- Home

- Mark Morris (Editor)

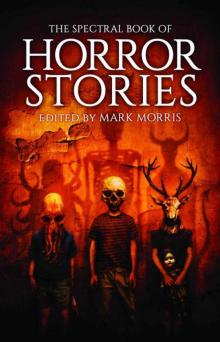

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Page 23

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Read online

Page 23

Franklin was incensed. “This is nonsense,” he said. “There is no way you have just carried out an accurate inspection of my life.”

“Oh, but I have.” Mr Norton scanned the two sheets of pink paper, poking his tongue out in concentration as he added the marks up with his biro. He wrote a number at the bottom of the final page and then gave Franklin a very solemn look.

“Mr Chalmers, I am very sorry to have to inform you that by the process approved by Her Majesty’s Department of Life Inspection you have failed.”

“Failed?” Franklin said with a snorting laugh.

Mr Norton regarded him without any emotion whatsoever.

“It’s no laughing matter, Mr Chalmers. I know this sort of thing doesn’t happen very often, but when it does, we believe the occasion should be treated with rather more seriousness than you seem to be giving it.”

Franklin got to his feet.

“I’m not treating this seriously because it’s bloody stupid,” he said, grabbing the cordless phone from the mottled granite of the kitchen work surface. “Now get out of here before I call the police.”

Franklin punched 999 and put the handset to his ear.

The phone was dead.

Franklin tried again.

Silence.

“Bloody thing.”

Franklin rammed the phone back into its cradle and took his mobile from his back pocket.

No signal.

Mr Norton didn’t move, but he did assume a slightly more sympathetic expression.

“You can’t telephone anyone, Mr Chalmers.” His voice was softer now, his manner appropriate for dealing with someone who has suffered a recent loss.

“Rubbish!” Franklin made his way into the hall where there was another telephone.

That was dead too.

“There must be a problem with the lines,” he said as he replaced the receiver.

“There’s no problem with the telephone,” said Mr Norton, who had followed him with silent steps. “The problem is with you.”

“No,” Franklin pointed a shaking finger at the little grey man. “The problem is with you, my friend, and you have just gone one step too far.”

Franklin turned and opened the front door.

To be confronted with the black, yawning gulf of absolute nothingness.

He slammed the door shut and looked out of the window.

Through the patterned glass Franklin could see a normal street. His street. The street where he and his family had lived for the last three years. The sun was shining. The old lady from number 37 was taking her terrier for a walk. The damn thing was shitting where it always did.

He yanked open the door to shout at her, like he always did.

Black nothingness lay beyond the gaping doorway.

Mr Norton allowed Franklin to repeat the door opening and closing ritual another three times before he spoke again.

“You can’t leave the house,” he explained, “because you don’t exist.”

“I don’t…”

“…exist. Therefore you cannot interact with the real world. You failed your life inspection. Therefore you no longer have a life. Believe me, I don’t enjoy failing people and I’m very sorry, but that’s just the way it is.”

Franklin looked out through the glass once more. The old lady and her dog had gone now, but he could hear the animal yapping. At the postman, probably.

The postman!

Sure enough there he was, and God bless him he had a handful of stuff to shove through the letterbox. Lovely circulars, wonderful bills—anything as long as they gave him the chance to communicate with another person.

As soon as the letterbox began to open Franklin screamed. It was a long, drawn out plea for assistance that began with the force of a bear but quickly tailed off into a sorrowful whine.

The second time Franklin tried all he got was the sorrowful whine.

The third time he got nothing.

“I’d save my breath if I were you,” said Mr Norton. “You don’t need a voice anymore, so it’s not going to last much longer.”

Franklin looked down at the envelopes that had fallen through the slot.

The envelopes that showed that someone else now resided at this address.

“Why?” he croaked.

The word was little more than a whisper, a dying breath stretched out across forty-five years of existence, of successes and disappointments, all to be rendered invalid because somehow, in some way, he had failed the most important test of all.

“I wish I could tell you, but I’m not allowed to, and it’s not as if it’s going to make any difference. Besides, it would take me longer than you have left.”

“What about my… my…”

“If you don’t exist then your family can hardly exist either, can they? Your children have already gone and your wife has been reassigned. You’d be surprised how easy it is to adjust the world so that the removal of those who fail makes no difference whatsoever.”

Mr Norton squeezed past the fading, wraith-like figure that had until recently been Franklin Chalmers. He had his hand on the front door handle when he stopped.

“Goodness me, I almost forgot,” he said, tearing a perforated strip from the bottom of the form and handing it to the nebulous transparent shape, which, despite having already lost most of its higher thought processes, still possessed the instinct to take it.

“Wouldn’t want you becoming a ghost now, would we?” Even though it would not be able to register it, Mr Norton gave the fragmenting shape a smile before stepping out into the street.

Once outside, the Life Inspector took a deep breath of the fresh mid-morning air, allowed himself a moment to appreciate the clear blue sky, and then consulted his clipboard once more. After all, he had a quota to fill by the end of the morning.

“Right,” he said to himself. “Who’s next?”

SOMETHING SINISTER IN SUNLIGHT

Lisa Tuttle

Another sunny day in L.A. It was getting him down—the weather, along with everything else. There was something sinister in sunlight. Not so much in England, when the weak, gentle sun made a special appearance, but day after day, unrelieved by clouds or rain, it struck Anson as unnatural. He found it just as perversely oppressive as the regulation smiles and bonhomie of store clerks and waiters. “Have a nice day, now!” It made him homesick, nostalgic for sullen youths with bad teeth, too proud to pretend they enjoyed being your server, while he missed the soft grey skies and sodden ground.

He’d created a whole little schtick about it—made Harry laugh when he’d skyped him—but it had fallen flat when he’d tried it out at a poolside party yesterday. Americans: they didn’t take offense; they just didn’t get it. The English sense of humour. British comedy was supposed to be big in the States just now, so maybe it was him. He wanted to prove his versatility, show another side to his character, and it didn’t work. Producers, directors, audiences wanted just one thing from him, the same performance again and again. Maybe it was the best he could do. Who was he to say they were wrong?

He thought of his last conversation with his agent.

“So you’re saying I should be grateful for whatever I’m offered?”

“Of course not, Anson. But those last two—they weren’t bad parts—and not inconsiderable.”

“They were the same part. Serial killer. Sinister, high-functioning sociopathic murderer.”

“Well, you’re very good at that. And you bring something to—”

“To an underwritten, clichéd part? I should bloody well hope so. Jay, it’s depressing. Why can’t I do something else?”

Jay had been silent for a worryingly long time. Afraid his agent was trying to come up with a new, more palatable formulation of the bitter truth, he had jumped in first.

“Look. I’m not saying I have to be the lead. I don’t mind being the villain. I just want to do something different—something that is not just another replay of Cassius Fucking Crittenden.”

Originally, the villain was slated to die at the end of the first season. But his character was too popular; so, in the second season it was revealed that the serial killer had survived his apparent immolation in a burning car, and he returned to taunt the detective hero.

In retrospect, Anson felt he should have walked away after the first season. As a character, Cassius had always been fond of masks and disguises, and the circumstances of his ‘death’ meant it would have been easy enough to use burns, scarring and plastic surgery as an explanation for the appearance of a different actor. But to walk away from a sure thing, from regular work—extremely well-paid—to return to the insecurity of the acting life was not in his character. And so, even though he’d never liked Los Angeles, he had stayed—for six years.

Six years on the series, and then it ended. It had been a relief to get back home, wonderful to have the freedom to do whatever he wanted. For a little while there had been plenty of offers; he could take his pick. He didn’t have to go back to L.A. There were films, a role in a David Hare play, a TV series set in the 1960s, in which he played a hard-bitten yet soft-hearted journalist, and a string of smaller parts, which grew smaller and less frequent as the years went by.

Somehow, nothing else he did ever attracted the same attention. They were like a succession of wrong turns, each one leading him down a one-way street in a further wrong direction. Until finally it seemed he had never done anything noteworthy or memorable except play the continuing role of a psychotic killer on a popular American TV series. The roles he was offered became depressingly similar.

This trip to California, urged by his agent, now seemed to him the worst wrong turn of all, the final nail in the coffin of his career. If he was remembered at all, it was as Cassius Crittenden, and that memory fatally coloured the perception of every casting director, every producer, every show-runner… they could not imagine him, Anson Barker, successfully filling any other role. Didn’t these people understand about acting? Or… was he kidding himself? Maybe he just wasn’t any good.

Self-doubt, self-pity, all the personal fears came out when he was alone at night, like roaches through the floorboards and invisible cracks in the walls of the borrowed apartment.

He wished he was home, where he didn’t have to cope with the eight-hour time difference before he could talk to Harry—where he could be in Harry’s arms, not just looking at him on a screen—where he could call up some of his mates to meet for a drink, or just drop in to a pub or a cafe, one of the places where he was known—and not as the actor who used to be Cassius Crittenden.

He wished he had never come. But now that he was here, he had to see it through. A few more days, one last meeting, and then he’d put it all behind him, go back to London, find something else to do.

Making an effort to shake off his depression, he went out for a late breakfast at the Blu Jam Cafe. It had become a comforting habit—just a ten-minute drive, and French toast to die for.

It was crowded—closer to lunchtime than breakfast, he realised—and the waiter had just told him there’d be a half-hour wait, then paused and said, “Unless you’re joining… her?”

Anson had not noticed the woman giving him a wave from her corner table, and once his attention had been drawn to her, he did not recognise her. But it was instantly more appealing than either going away or hanging around on the sidewalk for half an hour, so he agreed.

She was mid-thirties, he guessed, with sharp, not unattractive features, bright blue eyes, glossy, wavy auburn hair. She wore a bright blue blazer over a white shirt—something about the ensemble said ‘estate agent’ to him, although insurance or low-level finance seemed equally possible. She was vaguely familiar, but he still couldn’t place her.

“You don’t remember me, do you, Anson?”

“Sadly, no—but I shan’t forget you again, I promise.”

She stretched out her hand. “Elissa Condé. We met at Jack and Aura’s party?”

“Of course. You’re an architect.”

She smiled so tightly it seemed more a grimace. “Good to know I’m not utterly forgettable.”

He remembered her profession because Harry was an architect—and because he hadn’t quite believed her. The other thing he remembered about her—now, and too late—was that she’d given off a crafty, vaguely stalkerish vibe; pretending to have no idea who he was, and asking none of the questions people normally asked when you said you were an actor. But she knew who he was, all right, he had seen it in her eyes, and she hadn’t wanted him to know she knew. She wanted him to think their meeting was purely accidental—like this one—when in fact she had engineered it for her own purposes.

He felt a prickle of excitement. This woman might be dangerous… but he wasn’t afraid. What could she do to him? She wanted something, and she thought he didn’t know, whereas in fact he had the edge—he didn’t know, but neither was he fooled. And it might be interesting to find out what she was up to.

He ordered the crunchy French toast and coffee; she asked for organic granola with soya milk, and a pot of green tea.

When the waiter had gone, Anson treated Elissa to a kindly, avuncular gaze. “I’m sorry I had to abandon you so abruptly at the party. It must have seemed very rude. But I wasn’t there to enjoy myself—it was all business. But now, here we are! We can make up for our missed opportunity. What would you like to talk about?”

She seemed a bit taken aback by this approach. “Oh, I don’t know… what do you think of L.A.?”

“The traffic is even worse than it was when I lived here. Not my favourite place, I have to say. I’m looking forward to going home next week.”

She looked worried. “Where’s home?”

“London.” He drummed his fingers on the table. “What about you? Native Angelino?”

“Pretty much, yeah.”

“And you like it.”

“Sure. It’s okay. I mean, I don’t really know, because I’ve never lived anywhere else.”

“Travel much?”

“Some. But I hate flying.”

“Sing it, sister! But what can you do? If you want to go anywhere…”

“I drive. It takes longer, but not always, when you consider the time you save hanging around in airports.”

“That wouldn’t work for me.”

She looked at him blankly. “Why not?”

“London, remember? Can’t drive across the sea.”

“Oh, right. I wasn’t thinking…”

“You’ve never been abroad?”

“I’ve been to Mexico.”

“OK. Did you like it?

“Cozumel was pretty nice, but really, I wouldn’t go again. It was my boyfriend’s idea—my boyfriend at the time. I’m not with anybody now. But I mean… why go to Mexico, when you can get the same stuff here? The restaurants here are better. And for scenery—I’d rather go to Taos, or Monterrey.”

He was baffled by her. Conversation was hard work, and she seemed strangely incurious about him—about everything, really. Or else she was keeping a really tight grip on her emotions, fearful of giving away her secret. What was her secret? That she was obsessed by him, in love with him, imagined they were soul-mates… or, more drearily, she’d written a script, had an idea for a series, thought he could get her an acting job? Well, she’d have to tell him eventually. To his own surprise, he was actually curious. Instead of being bored,

he found himself touched by a deep, unexpressed sadness in her. The dreariness of her imagination somehow put his own worries into perspective.

Finally, television entered the conversation. Elissa became more natural, and openly enthusiastic, as she talked about her favourite shows, one of which, it came as no surprise, was the one Anson and Harry had taken to calling ‘That Which Shall Not Be Named.’ Yet still she said nothing that could be taken as an admission that she knew Anson had played the part of Cassius Crittenden—not even when she invited him to her house for dinner.

“You have to. Come on, don’t try to wriggle out of it. You’ve already said you’re not doing anything on Friday, and you’re fed-up with take-outs. Blu Jam is closed in the evenings, and even if it wasn’t, man cannot live by French toast alone.”

That startled a laugh out of him; she was nothing like as dull as she’d seemed at first. Yet the prospect of spending an entire evening alone in her company made him uneasy.

“You said you liked Italian food. Well, let me tell you, I make The. Best. Lasagne. Ever. And there’s somebody I want you to meet. Somebody you have to meet. You’ll thank me for it.”

“Really? Who is this paragon?”

“You have to come and find out.”

He wagged a reproving finger. “You had better not be trying to match-make. I’m a happily married man.”

She went pale, and he realised he had genuinely shocked her. “You’re not!”

“Well, no, not really.” He gave her a somewhat puzzled smile. “You’re right. Same-sex marriage isn’t legal quite yet, and I must admit Harry and I didn’t sign up to a civil partnership, but we’re quite the devoted couple, even so. Been together three years and six months. I’m not looking for anyone else.”

“You can’t be gay.”

He put his napkin on the table, too cross and weary with her stupidity to respond.

“Cassius isn’t gay!” It was a cry from the heart.

He had to laugh, although he wasn’t amused. “No, no, Cassius isn’t gay—nor is he English—nor real. It is called acting.”

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories