- Home

- Mark Morris (Editor)

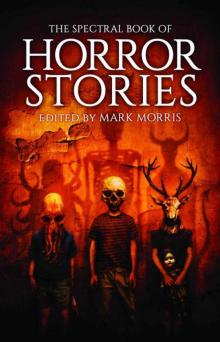

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Page 16

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Read online

Page 16

Back to that R—O—G in their name: They’ve got it backwards. In the world of so-called extreme metal, you can’t swing a ritually sacrificed cat without hitting some band with G—O—R in its name. I looked it up so you don’t have to. Gorgoroth. Gorguts. Gorefest. Belphegor. Cirith Gorgor. Don’t make me go on. So what I humbly suggest is that the brainiacs in Balrog change their name to Gorgonzola, so they can quit dicking around and lay claim, once and for all, to the title of Cheesiest Metal Band In The World.

And that was that. Mr Sunshine folded the papers again and, when Tomas made no move to take them back, set them on the grass, lightly, as if hoping they might vanish in a puff of fairy dust.

Tomas stood with folded arms. “You never even listened to the review copy, did you?”

Getting through the reading without another kick in the ribs seemed to have given him a little fire. “You’re so fucking wise and all-seeing, what do you think?”

“I think it was a rhetorical question,” Tomas said. “They’re all like that, aren’t they? Your ‘reviews’. Every line trying to be more insulting than the line before. I got bored looking for anything different before I could find it.”

“You’d be looking a long time.”

“I’m curious,” Tomas said. “Did you aspire to be a sham all along, or did that just happen? There’s no other word for it. Sham. You occupy a position that implies objectivity, but your mind is made up about something before it even occurs to the creator to create it. Your hatred isn’t just cowardly. It’s lazy.”

One corner of his mouth curled into a self-satisfied sneer. “It’s consistent.”

I’d already figured him for the kind that couldn’t lose. The readers who lapped it up, thought his shtick was the funniest thing they’d ever seen, that was pure validation. But so were the ones who thought he was a plague, and took the time to say so. The more pique in their comments, the better. Attention was attention. He was the kind who’d find scorn just as nutritious as praise.

As long as no one was actually holding him accountable.

So when Tomas squatted next to him, Derrick began to squirm with unease again. Tomas could go a long time without blinking. Silence didn’t bother him. Eye contact didn’t bother him. He was a master of simmering hostility.

“The hatreds I have, I come by them honestly. They’re considered,” he said. “Let me tell you a few of them. I hate smug little hipsters in retro cardigans and thick black glasses. I hate disingenuousness. I hate people who say ‘my bad.’ I hate people who lack the courage to back up their professed convictions.” He pushed his hair back out of his eyes so nothing got in the way of the glare. “All my hatreds, they’re earned. I’ve put the time and effort into cultivating them. They’re pure. But you… you dishonour that ethos.”

Now, finally, Tomas took back the printout, although he didn’t unfold it. What he needed was already in memory. “Do you get off when people quote your own words back to you? ‘I’d rather be staked out spread-eagle while Satan’s most incontinent he-goat takes a steaming infernal dump on my face than listen to another minute of this.’ When I read that, I didn’t see hyperbole. What I saw was you laying down a challenge for yourself.”

Tomas stood again, as, moment by moment, Derrick started to put the pieces together.

“You may find this disappointing, but Satan is about as real to me as Saturday morning cartoons. You might’ve even picked up on that if you’d bothered to look into the album a little.”

Still weakened by his hours of sedation, Derek was in no condition to put up a fight as Tomas dragged him by his bound ankles halfway across the meadow, where a quartet of iron stakes was already driven into the ground.

“But I do believe in goats,” he said. “We’ll start there.”

There wasn’t much of a struggle even when Tomas lashed him, limb by limb, to the stakes, although he had plenty to say to Tomas’ back as he walked away.

It was when Tomas reappeared, leading the shaggy, horned thing from the barn, that Mr Sunshine really started to squeal.

#

The band was based out of Seattle, but hardly anyone knew about this remote place that Tomas Lundvall owned high in the Cascades, across the border in Oregon. The rest of the band knew. I assumed there was a real estate agent who knew. Now I knew. And, naturally, so did Mr Sunshine—not exactly trustworthy inner circle material.

“When you told him that nobody’s going to believe him,” I said to Tomas later, inside the cottage’s kitchen. “I need to know you mean that. I need to know there’s not going to be blowback from this once we get him back home. This is the kind of thing that the term ‘federal crime’ was invented for.”

Tomas looked amused. “Isn’t it a little late to start looking for assurances now?”

“I trusted you on faith when that’s all there was time for. I never said details wouldn’t matter.”

“No, you didn’t,” Tomas said. “He can talk all he wants, if he’s not too afraid to do it, and it’s only going to sound like so much delirium. He’ll never know where he’s been, exactly. You’ll drop him off outside an emergency room, and with everything in his system, it’s only going to look like he’s been on a bender for a few days. While he’s gone, there’s somebody in Chicago still using his ATM card once or twice a day. And his phone. There are pictures on the phone from a couple nights ago at the club, and he’s having a good time. There’ll be a few more by the end, too blurry to make out. It’s all time-stamped. He’ll have it all with him again by the time he lands at the ER.” Tomas see-sawed his upturned hands like a balance scale. “Which would you believe?”

A bit later, as the sun was starting to fade, Tomas went out to hose Derrick Yardley down and get him moved from the meadow into the barn for the night and take him a plate of food.

He was quiet now, had either screamed himself hoarse or given it up hours ago as pointless. There was no one coming, no one to hear. The nearest neighbour seemed to be at least a mile away, along winding roads, while the hills and valleys would contain almost any mortal sound.

This was land made to shield miseries from view, and keep them secret.

The place seemed as if it might have first sprung up as some long-ago settler’s homestead. The barn may have even been original, minus repairs, although the cottage was clearly newer, a replacement built on the foundation of the original. Its rustic nature seemed more by design than scarcity, and it was solid through and through, built of heavy timber, with a lot of stonework, too, including a rock fireplace that would have fit right into a hunting lodge.

As a getaway home, it was an unusual choice. Retreats, for those who could afford them, usually meant luxury and ostentation, oceanside villas and penthouses thirty floors above the great unwashed. I didn’t have to be Tomas Lundvall’s accountant to know that, even after seventeen years of second-tier success in the music industry, he didn’t have that kind of money… but then, he didn’t have those kind of aspirations, either. He had no use for a place that others would look at and envy. Instead, I figured, he would need a place to exile himself from the stink of humanity.

He was back in the cottage after a few minutes.

“You’re just going to leave him by himself all night?” I asked.

“If you’re worried he’s going to get away, you can join him and keep watch. As for myself, I have faith in the chain and the anvil.”

I wasn’t expecting that. “You’ve chained him to an anvil?”

“It’s a very big anvil.”

He looked at me then as if studying me. It was blatant. All these years of working for the band, and I’d never managed to decide if he did that with people because he was assessing what made them tick, or forever looking for something he was missing.

“End of the tour leg and all,” he said. We had a month of precious downtime before heading to Europe for the summer festival circuit. “Are you sure you don’t have someplace better you’d rather be?”

“Apparently I

don’t. But you know that already.” I’d married late, and even then, because of all the time on the road, it hadn’t lasted. I wouldn’t try again until I was a stationary target, if there was someone out there who would even have me by then. “You did ask for my help with this, remember.”

“It wasn’t part of your job description. You could have said no.”

“I figured you would’ve gone through with it anyway. I didn’t want to hear about it going wrong because somebody else fucked it up for you.”

He appeared pleased by this. Although even I wasn’t sure if it came out of a warped sense of loyalty or just the challenge of it, to see if I could get away with this madness. Had I really become that bored with life? That desperate to avoid going home to an empty apartment before helming the next leg of the tour got me out again?

“Having second thoughts?” Tomas asked.

“It’s just a lot of trouble to go to, and a lot of risk, to get back at some prick who said nasty things about you.”

He looked at me as if I didn’t understand anything. “It’s not about revenge. Punishment is only a means to an end. He needs to be educated. He needs to be corrected. If I feed his own words straight back to him, then maybe he’ll realise he should use them better in the future.”

“And you don’t think this is a little excessive?”

“The stove has to be hot if you’re ever going to learn not to touch it.”

“I’ve only ever heard that about kids,” I said. “He’s not a kid.”

“Exactly the point,” Tomas said. “He’s not a child, but he’s still no better than a baby who’s just learned to stand up and reach a wall so he can smear it with whatever he’s managed to scoop out of his diaper. There have always been people like that, but they were ignored by most people who recognised them for what they were. Now… now they set the parameters of conversation. They’ve found each other. They try to outdo each other in pointlessness, and their last allegiance is to the truth, or even accuracy, if that means it would take three more minutes of their time to check. They set the agenda. They have a voice that drowns out whatever remains of basic intelligence and actual thought. They’re the human equivalent of a car alarm that won’t shut off.”

“And you’re educating exactly one of them.”

But Tomas seemed unconcerned by the math. “Even the longest symphony starts with a single note.”

#

Day two: “I would rather scarf up a rotting platter of serpent roadkill scraped off the Highway To Hell, tail-to-head, washed down with a bucket of demon jizz.”

Tomas held him to it.

It wasn’t anything I wanted to see, so I’m not sure what he had prepared, exactly. In contrast to yesterday’s ordeal, this was something that required Derrick’s active participation, rather than passively lying on the ground as it happened to him. Which explained the taser that Tomas took with him to the barn. Cooperation now meant coercion.

So no, I didn’t want to see it. But I could hear it.

Mr Sunshine was in stronger voice this morning, and I could clearly make out what he was saying when he shouted that he would listen to the music, for fuck’s sake, he would listen all day, it had just been figures of speech, exaggeration for laughs, just empty words, nothing that any sane person would take seriously.

He still hadn’t grasped that it wasn’t about that at all.

From the kitchen table in the cottage, still working on morning coffee, I found it a one-sided conversation. I couldn’t hear anything Tomas said. I once heard him profess that he wanted whatever he had to say to be worth straining to hear, and so it must have been in the barn. Wrath, with him, was not coloured red. It was the blue of glacial ice.

All I could hear were the sounds of pain, and soon the sounds of sickness, of gagging and retching, broken up by wails of utter despair. It came and went in cycles, as if after a certain point Derrick Yardley was too stricken to go on, and Tomas allowed him time to recover before resuming the putrefied feast where he’d left off.

It went on all morning.

You could call such things a taint on what was otherwise a glorious late spring morning in an unspoiled paradise. But they only augmented and enhanced something that was already there.

I didn’t like this place.

After twenty-three years of reducing world travel to a daily grind, I’d developed a sensitivity to places. I don’t know how, it just accrued, an awareness of what certain places had absorbed and what they exuded. Clubs and concert halls radiate an energy from all the performances they’ve hosted. Hotel rooms are mostly soulless and anonymous, but now and then I’ve stepped into one that’s toxic, and known that something very bad happened there.

Here, though, it wasn’t the cottage so much as everything else.

I could step outside and come face-to-face with it, in any direction, until it drove me back inside for the illusion of refuge. It was in the hills, and the way they seemed to leer down in curiosity and contempt. It was in the trees, and the way so many of them grew twisted even though they were sheltered from the corkscrewing gales that would have done this to them. It was in the rocks and the way they weathered, as if some truer, crueller form were trying to break through. It was in the shadows, and the way they seemed to hide something, all but its piercing and inquisitive gaze. It was in the wind, and how it fell just short of an intelligible whisper that I feared I would learn to decipher if I stayed long enough. And when a torrential shower swept through that afternoon, it was in that, too, if only because, in conspiracy, it cloaked everything else and gave me room to doubt, wondering if it wasn’t just my imagination. Three months of exhaustion, jitters, and road nerves catching up with me all at once.

“What made you buy this place?” I asked Tomas that evening, as the sun went down on another terrible day in Derrick Yardley’s life, and we sat before the fireplace sharing wine.

“Don’t you know anything about real estate?” he said. “Location, location, location.”

“You know what I mean.”

Tomas nodded, studying me again. “So you’re cueing into it already. I wondered. I can’t say what most people are like because hardly anyone has been here and I want to keep it that way.”

“Somebody had to bring you up here the first time. What about them?”

“It was just another normal transaction for both of us. I sensed it was a good fit. I sensed that very strongly, but I couldn’t have explained why. I try not to be arrogant enough to think whatever’s in this place might have sprung up or settled here because of me, but it’s hard. That huge rock star ego, you know.” I caught a strong whiff of sarcasm. “Maybe some of both. We fed each other.”

I imagined him here alone, doing the things you would expect anyone in his line of work to do: recharging, decompressing after spending months meeting the demands of other people, writing new songs. Exploring, too; there was a strong undercurrent of nature worship in Balrog’s music.

But I could also envision him doing the sorts of things that you might not expect, not if you dismissed the band as nothing but creatures of hollow image.

They and I went back far enough that I took it for granted that their look, their sound, their lyrics, everything, was more than mere theatre. While theatre was important, it was still a reflection of something real. Ghast wasn’t just Tomas Lundvall’s stage name, a character he put on along with the leather and paint. It was a part of him.

“Balrog isn’t a band that’s about exorcising demons,” I once overheard him say in a backstage interview. “What we’re about is communicating with them.”

Sure, that could only be more myth making. Yet I believed he meant it. I was just never sure exactly where the lines were with him.

So I had to ask: “Am I even going to be taking Yardley back to Chicago?”

Tomas didn’t seem surprised by the question. “Why would you still be here if you weren’t?”

“To give me time to get used to the idea,” I said. “You

couldn’t have me just drop him off and turn around, because that would be admitting upfront that he wasn’t going to be leaving here alive.”

Tomas swirled his wine and held it up to the fire, mesmerised by its red glow. “Would it be a problem if he didn’t?”

“I didn’t sign on for that.”

“I know. The question is, what would you do about it?”

Could I take Tomas, if it came to that—was this the bottom line question here? Almost certainly I could. Yes, he was imposing, and almost fifteen years younger, but I was the size of a movie Viking and still had the muscle from back when I started as a roadie, along with fifteen years more experience brawling. We could both put a hurt on each other.

“I don’t know,” I finally said. “Yet.”

“Neither do I.”

“You sure you’re not just playing coy?” I almost jumped when, in the fireplace, a knot of wood went off like a rifle shot, in a shower of sparks. “I know what that review says. I know what’s coming tomorrow. Go through with that, and you’d be sending him back with physical damage.”

“And your point is…?”

“That makes it harder to square with him losing a week to a binge. He doesn’t just have a wild story now. He’s got real injuries, and, oh hey look, they’re exactly what he wrote about in his review of you. You’d be stupid to send him back with actual evidence. You know that.”

“You’re right. So maybe I shouldn’t.”

When shit gets real—I’d heard this expression for years, but had never felt the full weight of it until now. Finally, I recognised the real reason why I’d gone along with Tomas’ plan. I was in awe. Who would be crazy enough, committed enough, to do something like this? I could think of only two scenes. Some rappers, maybe. But it wouldn’t be this elaborate. Just quick payback, all about the disrespect. And then there was the darkest fringe of extreme metal, where they thought the devil was real.

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories