- Home

- Mark Morris (Editor)

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Page 17

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Read online

Page 17

Except Tomas didn’t believe in him either.

“Why don’t we name it,” I said. “Sacrifice? Is that what you’re thinking about?”

“That’s too simplistic a concept. But for the sake of discussion… okay.”

“Weren’t you just saying yesterday that the devil is as real to you as Saturday morning cartoons?”

“That’s why I called it too simplistic a concept.” He lingered a moment, as if he’d never had to explain himself before. “The way I see it, there are things infinitely older than any childish conceptions of god and some adversarial devil. There’s only chaos, and the manifest forms that come out of it, and the fleeting intelligences that guide them. Magnitudes of order rise and fall, and all we are are the building blocks it uses to make things and then topple them over to start again.”

He stared out at the dusk, and the only sound was the fire and, beyond the open window, the dripping of the newly ended rain from the eaves.

“I can’t say for certain what’s going on in this place,” he told me. “If it’s that the membrane between chaos and order is thin here. Or if it’s because, right here, the process has already reached its height on one side of the fulcrum, and now it’s started to drop the other way…

“I just know that, if you’re willing to put in the work, you can play with the other blocks.”

#

Later that evening I went out to the barn to see Derrick Yardley for myself. He was a disheveled figure huddled against a rough wall under the tepid light of a dangling sixty-watt bulb. Something else dangled from another crossbeam, low enough to hang tools on, but this one I had to stare at until I comprehended that it was the ragged, meat-stripped skeleton of a snake longer than my arm. The barn interior stank of bile and decay.

Across the dirt floor, in a pen, yesterday’s goat munched happily on sweetgrass. No place smells bad to a goat.

Mr Sunshine was as degraded a human being as I’d ever seen. A thick leather cuff was snug around one ankle and a ten-foot chain anchored him to a huge, honest-to-god anvil that looked like it had been around since the formation of the earth. In a radius around him, and on nearly every square inch of him, was the evidence of violent and explosive sickness.

“Fuck you too,” he croaked as I approached.

I offered him a plastic bottle with the clinical look of something that had come from behind a pharmacy counter.

He eyed it with suspicion. “What’s that? Something else for me to puke up?”

“It’s an antibiotic. Liquid ampicillin. He thought it would be a good idea.” I looked at the chunks and splatters in the dirt. “Considering.”

He grabbed it, uncapped and sniffed it, and took a sip.

“Not all at once. Just a swig or two every few hours.”

“I know how antibiotics work. Jesus. Now, if I just had a clock to tell me when a few hours have gone by.” He rolled his eyes. “Are we done here?”

I respected that he wasn’t feigning gratitude, trying to win me over, beg. No Stockholm Syndrome for him. It was business as usual: all spite, all the time.

“You’ve got a style to what you do. No denying that. I’m just curious why. Why take that approach?”

He stared at me like I’d spoken gibberish. “Why…? I don’t get the question.”

He really didn’t, did he? “What do you get out of it?”

Again, more incredulity. That little open-mouthed, side-to-side headshake when someone can’t believe he’s hearing such idiocy. “I get more hits than anyone else there. More page views, more sticky-time, more link follow-throughs. I win.”

Okay, I thought. Just as calm and clearheaded as could be.

Fuck this guy.

Maybe 90% of everything really was crap. I don’t know. But he’d made it his life’s mission to punish people for even trying, regardless of the outcome.

“Yeah,” I said. “We’re done here.”

Then, finally, I looked up into the hayloft, because I was starting to feel gutless for avoiding it, telling myself that whatever I’d heard shifting around up there was just a rat. Or a barn owl. Or a snake the size of a fire hose. Or any of the other manifest forms allowed by chaos. In that moment it looked like all of them, all at once, at least what I could make out from filling in the gaps between the shadows… until even the shadows unravelled, and perhaps there had been nothing to see after all.

So maybe Derrick should’ve paid attention to the music. He might have learned something: that in stirring up all that hate, he should’ve expected to someday summon up something worse than a simple ass-kicking.

#

Day three: “The prospect of performing acupuncture on my testicles with rusty needles is preferable to the idea of waking up tomorrow suffering the knowledge that this is still a world afflicted with a Balrog infestation.”

When you’re in, you might as well go all the way.

The day threw another downpour at us, and I was glad of it, the sonic insulation between my ears and what was going on inside the barn. The shrieking rose and fell, sometimes cutting through lulls in the rain. But for the most part it sounded far away, the kind of screams you’re willing to dismiss as coming from a neighbour’s TV.

At what point had I stopped seeing Derrick Yardley as human? At what point had this become irreversible? I had a long drive ahead to mull that over. My luggage was packed and ready to go, not that it took long. I’d been travelling light for twenty-three years… lighter than ever, now that I seemed to have left my conscience behind. Maybe I would find it at home. Maybe I’d lost it along some road I would never recognise if I travelled it again.

I stepped out the cottage’s back door and stood beneath the awning, staring through the watery curtain at the mouth of the barn. There was no sound but the rain. I wished Mr Sunshine a quick death. A meaningful death, as one of the building blocks of chaos and order.

I didn’t know what Tomas’ specific intentions were, and he hadn’t said, maybe because he didn’t want the embarrassment of committing to something he couldn’t deliver. Some kind of transfiguration, maybe. Some act of will that would send ripples through what he called the noosphere… the sphere of human thought. The world according to Ghast.

By now I was considering that I’d been wrong all along about what Tomas’ stage persona meant to him. I could see it, finally. It wasn’t so much that Ghast was a part of him but, rather, something he aspired to be.

And then he came out of the barn and walked up to me, standing there looking hesitant and soaked to the skin. His hair hung to his chest in sodden tendrils and he had to blink water from his eyes. Just another wet guy in the rain.

“Are you ready to take him back?” he asked.

“If that’s what you want,” I said. “What changed your mind?”

He started to say something, then shook his head. Nothing he wanted to articulate, to admit to. He just pushed past me, inside the cottage.

“I need to get the BZD, put him to sleep for the trip,” was all he said.

A part of me was relieved—the better part, I hoped. But another part of me was deeply disappointed. Because I was curious. I’d felt the currents churning around us, in the fabric of earth and rock and trees and sky. I’d seen something in the hayloft, be it manifest form or fleeting intelligence. I was ready to believe that nothing might be true, that everything might be permitted. Tomas—or Ghast—had persuaded me of that much.

So I wondered what would’ve happened next, if his nerve had held out a little longer.

Syringe in hand, Tomas—just Tomas—pushed past me again and returned to the barn.

And the rain hammered down.

I knew him well enough to suspect that this surrender of plans was something he’d want to handle without an audience, so I waited a couple minutes. Then a couple more. How long did it take to sedate one guy, anyway?

At least it doesn’t take any special powers to know when something’s not right.

So now it was my t

urn to get soaked to the skin.

I found Tomas on the barn floor, beneath the anvil. The enormous anvil heavy enough to anchor a man in place for three days. His chest and ribcage were as caved in as the bones of a serpent run over on the highway. But it hadn’t only hit him there. He’d taken a blow to the head, as well.

Put it this way: he no longer needed makeup to look like a nightmare.

And Derrick Yardley? He was as far away as ten feet of chain would allow, every last inch of it, wide-eyed and pressed against a support beam as if he wanted to merge with it. He was trying to talk. He just wasn’t there yet.

I looked up at the hayloft.

By day, the barn’s shadows retreated higher, and I followed them, drawn by movement that I sensed more than saw. But something was up there, and whether it scurried or flowed I couldn’t say, this malformed collective of rat and owl and snake… and now goat. The pen was empty. I followed its path up the sloping underside of the roof, until it reached the peak and kept going through the angled juncture, as if squeezing through a crack in time.

With nothing more to see overhead, I looked at Tomas again, not merely killed, but demolished. If I had to ascribe motivation to something beyond understanding, I’d have to say it was disappointed in him.

“It said it didn’t have much time,” Derrick Yardley finally got out, in a halting voice. “It said I’m more their servant than he ever was. What did it mean?”

He looked at me, pleading yet cunning, as if I were supposed to have his answers.

“What did it mean?”

When I left, I closed the barn door behind me, and would’ve chained it shut, except the only chain I knew of was attached to Derrick Yardley already. I had a sense that it wouldn’t matter for long, anyway.

As the rain let up, anyone could feel it in the air.

THE OCTOBER WIDOW

Angela Slatter

Mirabel Morgan suspected herself hunted, though she’d caught no trace of whoever pursued her.

She was careful when she left the house, keeping a weather eye on the rear-view mirror, but able to discern no particular vehicle standing out from those sharing the road with her. At night, she made sure to close the curtains well before darkness fell, when lights might pick her out as a target against the evening gloom. Yet no one appeared on the pavement or stoop, there were no raps at the door, no envelopes in the mailbox. No sign that she should flee. She watched the calendar tick over with inexorable certainty and, as the day paced closer, the grid of nerves inside her chest tightened like wires pulled by circus strongmen. Tendrils of white had appeared at her temples regular as clockwork, and her face, though still handsome, had crow’s feet radiating from the corners of her eyes, and lines formed parentheses from nose to mouth. The chin was less firm than it had been, but her cheekbones still soared high, kept her profile patrician. Her knuckles were swollen, like dough sewn with yeast and carelessly kneaded, furrows left embedded. They’d been aching since the temperatures had lowered, the same gnawing pain that afflicted her at this time. Made it harder to do things when she most needed to be agile if not sprightly. Every cycle she told herself that the next would be different, that she’d be better prepared. Yet each turning she did the bare minimum, ensuring the new abode was liveable, then went off to enjoy her annual youth while it lasted. In the garden, the leaves changed colours, swapped out their green for amber and yellow, ochre and sepia. Those so inclined fell and were carried off on the biting breeze. The sky, perpetually iron-grey at this point, was occasionally lightened by white clouds, however more often darkened to thunderous black. The vegetables and flowers had died, turned dry and shrivelled. She didn’t plant fruit trees any more for she moved so often, and hated to watch them wither prematurely as they inevitably synched with her eternal, truncated rhythm. The small town of Ashdown had served her well, and she in turn had served it, bringing all the boons attendant upon the October Widow’s tenure. The secret tithes she took seemed, to her, rather insignificant. The tiny offerings that staved off the moment when a larger one had to be made.

#

Henry did as he usually did and went straight around the back of the house, to the little shed where Mrs Morgan kept her hand-mower. He was late, but he knew the older woman wouldn’t mind. “As long as it’s done by nightfall on Friday, Henry, I don’t care what part of Friday you do it!” she’d said. But he liked to be reliable. He liked her to know that she could count on him. This morning his pickup had a punctured tyre; it looked as though a knife had been stuck into the tread, but he couldn’t for the life of him figure out who would want to do him an ill turn. He’d taken his brother’s battered VW instead of wasting time changing the flat.He began where he always did, out the front, with its tiny patches of grass broken up by flower beds filled with dead plants. The rose bushes looked especially sad, bare but for their thorns and the crinkled brown remains of red and pink blooms. The mower was stubborn, though he’d oiled it only last week, and took more than a few enthusiastic shoves before the blades loosened and did their job. He hated the thing, but enjoyed the workout it gave. If it were a bit warmer he’d have his hoodie and T-shirt off so the three teenage girls who lived next door could peek out and watch him sweat and glisten in the afternoon sun. But that time was done, the season passed. Too cold now for such exhibitionism; he had to keep his peacock preening to the public bar in the evenings until next summer.He moved into the back, which was the easier spot, the vegetable beds running along the side fences, out of the way, leaving the rest a clear run right up to the edge of the property where lawn met woods in a hard line. The garden did not gradually grow wild and blend into a creeping foliage that led to full-blown forest. Just ended in a stern demarcation line between the tame and the uncultivated. A creak and a tumbling sound snapped his head up to see three crows flapping and finding new perches; their previous branch had broken and hit the ground just as he looked. Black eyes regarded him, curiously, somehow fondly. There must have been something dead in the undergrowth he decided, or dying. They were waiting until it was weak enough.He reached the boundary and turned the recalcitrant machine. The curtains on the kitchen window twitched aside. Mrs Morgan stood at the sink, giving him a wide smile. She made the usual hand gestures: Come inside when you’re finished, I’ll make you a hot drink. And there’d be buns too, freshly baked, warm enough to melt the butter and run the thick raspberry jam thin. She’d put a little whiskey in his coffee: Irish it up, she’d say like she always did. And she’d smile and he’d smile back, watch her as she moved around the small kitchen, never still, but never hurried, always assured, seemingly always in the spot where she was meant to be. And he’d watch how her hips swayed, how her breath made the breasts covered by her lilac blouse shift up and down, how shapely her calves were beneath the hem of the black skirt. How her face was shaped just like a sweetheart, her lips full, her skin creamy, her eyes not quite blue and not quite green but caught somewhere between. How any wrinkles were shallow and made by laughter not loss. How graceful her hands, her wrists, her fingers were as they reached towards him to lead him upstairs so he might see to Mirabel Morgan’s other needs.

#

Cecil Davis, despite his grief and rage, had not become sloppy in anything but his personal hygiene. If the woman had gotten wind of his presence, she’d have fled, he was certain, no matter how invested she was in remaining in Ashdown. He’d tracked her for so long and, having found her, rented a house two doors down and on the opposite side of the street. It gave him an uninterrupted view of her property. He kept the curtains closed, but affixed cameras under the eaves, trained them on the woman’s cottage. The place had come furnished, which was convenient, but hadn’t mattered one way or the other to him. He’d have happily brought along the sleeping bag and air mattress he’d once used for camping and then, later still, for surveillance after…He’d even managed to plant a GPS tracking device on her car, something impossible to notice unless you were actively looking for it. He didn’t have to

leave his four walls, just stared at the monitors he had rigged up so he could keep an eye on her comings and goings while he still managed to run his software support business from a separate laptop. The business he’d hoped to pass on now had as its sole purpose keeping the money coming in to fund his mission.She was going by Mrs Morgan now, though his researches showed she recycled her names as she went, different ones each time, no discernable pattern, but he’d learned them, if not all then many. Knowing what to look for meant he had found her at last, though it took him seven years. Seven years of hacking utilities records, bank records, seeing patterns, recognising names, catching the scent. As much as anything it was his willingness to believe in strange things when no one else would.It had taken all his determination, all the internal resources that had made him a successful businessman, to keep him focused. To keep him going after…Of course, he could only watch the exterior of the house. He’d not gone into her home, couldn’t bring himself to do that, though he’d never admit it was fear. It was caution, pure and simple. Caution, he’d have said if there’d been anyone to talk to about it; if the police in Ottery St Mary’s had listened with anything but pity, or the parents in the other small villages he’d gone to after…The young man who did the gardening was there again, in spite of the penknife Cecil had stuck in the back tyre of his vehicle, trying to put an obstacle in his way. Cecil had to admit it hadn’t been a very effective obstacle. He was aware that if he approached the man, tried to tell him what he knew, he’d come across as a nutter; that the lad would back away, go straight to the woman and warn her. Though he’d let things like bathing and general grooming fall by the wayside, Cecil knew there were some illusions he needed to keep intact.He’d do what he could to protect the lad, within reason. He was someone’s son after all, and Cecil had no wish for another father, another mother, to go through what he had; to wake and find their boy gone forever, become no more than motes of dust on the wind. He blinked as thoughts of Gil, tall and strong, young and vital, made heated tears rise, made the tendons of his heart thrum deep and discordant.Cecil looked away from the screens, to the corner of the sitting room, where his gear lay in a pile. He still wasn’t sure what to take with him. He knew where she would be, where she’d been going these past weeks, the place she had been preparing. But he didn’t know what to take, what would work, he didn’t really know what she was.He only knew that when he confronted her there would be no words, no recriminations, no time wasting that might give her a moment’s chance to escape. He doubted she remembered Gil. He doubted she remembered any, certainly not by name. He suspected there had been so many she couldn’t keep track of them all.No. No words. Whatever he might say didn’t matter. Wouldn’t matter. It was only what he did tomorrow evening that mattered.

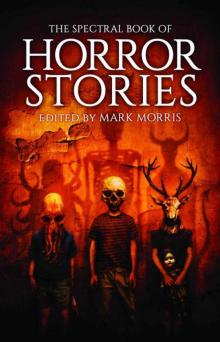

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories