- Home

- Mark Morris (Editor)

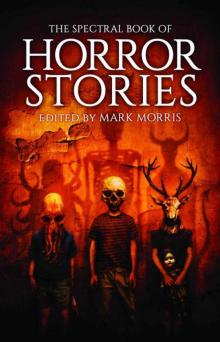

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Page 28

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Read online

Page 28

“Let him stay up there. A clip round the ear, he wants. He needs to be taught a—”

“Go and talk to him. Now.”

Bap bap bap! something went in the sky before fluttering and sparkling earthwards.

He could see she was upset, and more because of that than that he was in the wrong (he wasn’t in the wrong—bloody hell…) he went upstairs, unbuttoning his mac and draping it over the banister before ascending. Iris watched his hand, rendered pink by the cold night air, gliding up the wooden rail until his creaking footsteps reached the landing.

Her hair felt brittle and she tore through it with her hairbrush. The skin on her face felt tight, her throat felt constricted as if half strangled, her skull blocked and salty, all the usual symptoms after she’d been weeping or felt it was imminent. She still didn’t feel fully awake and hoped that the scene that had just happened was a dream, but it wasn’t, and she wanted to wish it away, and she couldn’t. Wishes didn’t work. She of all people knew that.

Brushing her hair didn’t do the trick. She needed to give herself a wash and headed upstairs to the bathroom, squeezing past the semi-rusted pushchair, the PENNY FOR THE GUY sign dumped in its seat at a skewed angle, and went up and give her cheeks a cold swill at the sink.

As she passed Kelvin’s bedroom on her way back down, she couldn’t help listening at the door. The man’s voice was soft and sympathetic. Loving, even. It didn’t sound like her husband at all. It sounded almost like the person he used to be. Almost.

“See, I say these things because I care about you, that’s all. I get angry because I just want you to be safe and sound. I do it for your own good, see. What you got to remember is, not all people are dangerous, but some are, and when you’re out on your own you don’t know who’s who, do you?”

She wished with all her heart she could see Kelvin’s little face and know how he was reacting, whether he was nodding or just listening, snuggled down in his bed under the eiderdown, but she couldn’t. After a moment of silence, Des spoke again:

“Hey. You done a good job. You and your mam.”

“Me, mostly.”

Iris smiled. Swallowed the lump in her throat.

“Don’t!” Kelvin gasped suddenly, bursting into panic. “Don’t move him!”

“Okay, okay, okay… Cool head… Here you are…”

“He wants to stay here and sleep next to me.”

“Orright, orright… Let me tuck you in then, nibblo…” Her husband’s voice grew faint as she padded downstairs, not wanting to reveal she was standing outside, earwigging the conversation. “You’re a funny ‘apeth.” Fading away, her son replied that he wasn’t. He wasn’t any kind of ‘apeth.

She switched on the TV. When it had warmed up it showed Mary Hopkins as a guest on The Rolf Harris Show on BBC1. Her trilling, virginal style of folk singing grated with Iris, in spite of her being Welsh and a discovery of Tom Jones—Ponty boy himself, bit of a boyo by all accounts, and without doubt the town’s only claim to fame. She wasn’t a big fan of the bearded Aussie either with his fair dinkum, down-under cheeriness. It always seemed entertainers were desperate to create happiness, but when the programme was switched off, where was the happiness then?

Presently Des came in, Schools Rugby tie loosened, easing the glass door shut after him, and sat in the armchair that was vacant—not the settee, which was always where she sat. Peculiar the habits you got set in. He sat in the glow of the screen. By the time she was crushing out a new cigarette in the ashtray she knew she had to speak, because she could hold it in no longer.

“Did you see the mask he bought?”

Des nodded, or flinched, she wasn’t sure which. “Grotesque bloody thing.”

“Why couldn’t he get a Guy Fawkes mask like all the other kids?”

“Who knows what goes through that lad’s mind. Honest to God. I give up. He can do what he likes.”

“You don’t mean that.”

“I don’t know what I mean.” Des rose from the chair as if the act was a gigantic effort. His pallor was grey. He looked exhausted. Emotionally drained. Even to talk, talk normally—to her—was clearly too much for him to bear. “I’m going to bed.”

Touch me. Touch me, she thought. Kiss me.

But he couldn’t. How could he?

Do I smell of blood? she thought, in the empty room, eyes fixed blindly on the television programme. Is that it? Do I, still?

#

On Sunday morning when Iris opened his bedroom door she found Kelvin with a snakes and ladders board laid out between himself and the guy, moving one of the counters up a ladder. When she asked if he wanted to come down the park for a walk, he shot a look at the guy—for all the world, she’d swear, as if deferring for an answer. None being forthcoming, he scuttled over and whispered via a cupped hand to the side of its earless head.

“He doesn’t want to stay in on a nice day like this, does he?” Iris said, persuasively, realising that her attempt to get her son to abandon the thing for a few hours was misguided.

Kelvin sat back on his heels. “Is Dad coming?”

“Not today. He’s got some DIY to do.” She didn’t elaborate on what they’d actually said to each other: her trying to persuade Des that getting out the putty to re-glaze a window in the scullery was not exactly a priority, Des insisting it was a job he’d put off for months, and that was what Sundays were for. If you say so, being her final, curt reply as she got her coat.

She helped the boy put on his shoes at the bottom of the stairs, the guy with its plastic smile perched a few steps behind him, as if sitting pillion. Observing through its holes for eyes. Observing her as she double-knotted the laces.

Kelvin rearranged the guy’s scarf, plumping the pillow in the pushchair behind its spineless back, evidently wanting the thing to be seen at its best.

“He likes sunshine.”

“Good.”

At the bottom of Mill Street they crossed the bridge over the Taff into Ynysangharad Park, the black water of the river below stark testimony to the industry of the Rhondda Valleys. As they passed the tennis courts—deserted at this time of year—she watched Kelvin run ahead with the pushchair at speed, with the intent of creating a thrill either for himself or, strangely, its immobile occupant, a figure that never looked straight or comfortable in its ‘chariot’ but awkward, ill-fitting, with an aspect of frozen entrapment reminiscent of a physically impaired child. It struck her horribly that, from a distance, a passer-by might take them for a family—especially the way Kelvin would regularly pause to tuck in a blanket around the thing’s bulbous, paper-filled legs, and whisper to it in a way that—no, it didn’t disturb her at all. Why should it? It was just play, and it was healthy for children to play, and use their imaginations. She just wanted to switch off her own.

The sticks of dead rockets lay on the tarmac, having fallen from the sky the night before. Their cardboard carcasses lay semi-charred and redundant—the spark of excitement they’d delivered now just a memory.

Iris buttoned her coat against the wind and stuck to their customary route past the cricket pavilion and band stand, inside which a small vortex of yellow leaves did a pirouette, and Iris paused to sit on a bench near the playground next to the mini-golf where Kelvin usually played on the slide and swings. She indulged in her last Embassy in the packet and opened the Woman’s Weekly from her bag, but after a few minutes the words, “Penny for the guy… Penny for the guy…” made her look up.

To her dismay she saw that, far from playing with the other children, Kelvin was standing with the pushchair at the gates to the playground, delivering his repetitive litany to every adult who entered. He didn’t seem unduly bothered by their disinterest and his mantra continued undiminished. This upset Iris more and more, as she saw the perplexed and then bemused looks on peoples’ faces quickly turning into expressions of unease and pity as they hurried their own children in the opposite direction.

“Penny for the guy… Penny for the guy…”

Iris hurried over and took Kelvin’s hand. “Come on. Let’s go home, love. It’s getting a bit cold and I need to get a cooked dinner on for your father…”

Heading towards the bus stop they passed Woolworths, its window resplendent with a vast display of Brock’s fireworks boxes, gaudy and brash, and a cardboard cut-out Guy Fawkes in an Elizabethan ruff and tall hat, holding a sparkler like a magic wand. Kelvin gazed at the arrangement with what she first thought was wonder, but then saw was more of a worried puzzlement, and from being chatty all afternoon the boy became suddenly silent.

On the bus she tried to lighten the mood—her mood, if nothing else—by unwrapping a tube of fruit pastilles and offering him one.

“I don’t like black ones,” Kelvin said. “But he does. He loves them.” He took a sweet between his thumb and forefinger and pressed it into the mask’s mouth, then turned to his mother and popped an orange one into his own, grinning broadly.

Iris was looking at the little boy and his guy, side by side next to her in the back seat of the bus when the stout, greasy-haired conductor arrived, ticket machine thrusting from his midriff.

“One adult and two halves, please,” she said.

Kelvin’s grin spread into a laugh, and Iris smiled too, before she saw an elderly woman with the face of a boxer dog who’d been kicked up the bum by Sonny Liston was giving them a look like they were insane, or beneath contempt, or both.

“What are you staring at?” Iris said, and the old woman turned her considerable chin—or rather, chins—in the other direction.

Kelvin was still chuckling at this as the bus changed to a lower gear halfway up the hill, taking the wide, hair-pin curve from Graigwen Place into Pencerrig Street. But Iris was glad he didn’t see what she saw, and what made her own smile fade very quickly. From the side window and then the back window, she got a passing glimpse up the rocky path leading to the quarry, where a large wigwam-like structure was taking form out of assorted planks of wood, fallen branches, sawn-down tree trunks, and pieces of discarded furniture. Even now a man dumped more wood on it from the boot of his car, and was dwarfed by the structure. It must’ve been fifteen foot high already, if not twenty. And to Iris—she didn’t know why, or rather she did know why—resembled nothing so much as a funeral pyre.

#

Still in his pyjamas, Kelvin brought down the guy and sat it on the settee while they all had breakfast. Des and Iris looked at each other but neither said a word. Kelvin was humming happily, his bare feet dangling under the table as he spread Marmite on his toast. Finishing first, Des picked up his car keys for the Anglia and said he was off. Iris didn’t expect him to kiss her, and he didn’t.

“You’d better run up and get dressed if you’re not going to be late,” she told her son. “Hang on. Aren’t you going to take him back to your room?”

“No.” Kelvin shot a glance at the guy. “He wants to stay down here today. He wants to keep you company.”

Iris stared at the plate in front of her, not wanting to look at the dummy in case the dummy was looking at her, and rubbed her bare arms before faking a smile through clenched teeth. “That’s nice.” Then calling, “Don’t forget to brush your teeth!” Then, in the silence, tried to address the remains of her toast but wasn’t hungry and pushed it away. It was scorched. Black. She hated that. Bread tasting like coal, because coal tasted like death. Her grandfather had worked down the mine all his life and that’s what he smelt like, however much carbolic he used to wash it off him.

Ten minutes later, when Kelvin came back down in his smart school clothes—corduroy trousers, V-neck, parka—she was sick of looking everywhere but at the thing half-sitting, half-lying on the settee. With a freshly-lit cigarette in her hand, she said:

“I’m not sure this is a good idea, love.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know what to do with him, that’s all.”

“Just make him feel at home. Just give him anything he wants.”

“What does he want, though?”

“He might want the radio on.”

Iris hid a laugh in a sigh. “Oh, I see. Okay. What kind of music does he like?”

“Any kind.”

The front door banged and the house was hers. Whether she liked it or not. She looked for the Senior Service ashtray— relic of The Collier’s—found it.

She switched on the transistor and it played Yellow River by Tony Christie and, by the time she’d finished the washing up, All Kinds of Everything by Dana. Drying the last teacup, she looked round the corner of the kitchen into the sitting room to see the settee side-on, and the guy hadn’t moved. Of course it hadn’t. How could it move?

She spent half an hour in the kitchen, tidying what needed to be tidied and wiping down the fablon surfaces and the hob of the oven, when she realised abruptly she was lingering there because she didn’t want to go back into the sitting room, which was pathetic and silly. As an act of defiance, to her own nonsensical fear if nothing else, she strode back through, not even looking at the horrible object—though one of its socks brushed against her calf—and went into the hall to get the Hoover out from under the stairs. She shut the door behind her, but couldn’t help seeing the vague, rippled shape of the occupant of the settee through the semi-opaque glass. As she moved her head from side to side it almost gave the illusion it was…

She carried the vacuum cleaner up to the landing and gave all three bedrooms a good going over. She didn’t enjoy housework, but she was house proud—got that from her mother, never a speck of dust on anything—and she was a good worker, and soon lost herself in the mindlessness of the task. By the time she came back downstairs an hour later she’d forgotten the guy and when she saw it gave a start.

Bugger!

Left tilted at an angle, the gnomish creation had now slumped on its side and gave every appearance of snoozing, impossibly, behind its plastic grin.

Annoyed at her over-reaction, Iris grabbed it and dropped it unceremoniously on the carpet, leaving it a discarded and distorted sack while she vacuumed the upholstery, after which she sat it back in position, puffing the scatter cushions around it.

The machine droned and sucked. Afterwards she stood breathless with the spout of the appliance in her hand. The mask was looking at her like she was stupid. Like it knew something she didn’t.

Sod you, she thought.

She desperately wanted a smoke. She poked the ‘off’ button with her toe and went to get the packet of Embassy from the mantelpiece, but it wasn’t there. It wasn’t on the stool next to her armchair either, which was always where she put it. It wasn’t in the kitchen and it wasn’t on the small table next to the telephone. She scanned the room, turning in a circle twice, but her eyes only fell on the inscrutable guy with its listless neck and hollow fingers in its freshly puffed-up throne.

“What have you done with my cigarettes?”

She didn’t mean it literally, of course. She was just voicing her frustration at not finding them. But she found herself saying it again, out loud:

“What have you done with my cigarettes?”

It was mute. It had no lips. It had no voice.

She knew it didn’t.

But when she made herself a mid-morning cup of coffee she didn’t have it in the sitting room, she took it in the front room, the posh room, and drank it in the quiet away from the radio there, without opening the curtains.

#

When Kelvin came home he burst past her as if she didn’t exist, went straight into the sitting room and emerged almost immediately with the guy, his arm hooked round its midriff, trailing it with him as he hurried upstairs, its baggy limbs flailing. The bedroom door slammed. It would have been nice for him to say hello or to tell her about his day in school, but that was fine if that was the way he wanted it. She went back to her ironing.

At five to five she gave him a shout to tell him Blue Peter had started. There was no reply. She called again, louder, from the foot of the stairs

but heard nothing but a solemn and disinterested, “Okay.”

Twenty-odd minutes later the show finished with the usual chirpy goodbyes from Val Singleton, John Noakes and Peter Purves and its distinctive hornpipe theme music—but Kelvin still hadn’t come down. Iris went upstairs to see what was so important to keep him from one of his favourite programmes.

As she approached the bedroom door, hand raised aloft to rap it with her knuckles, she frowned and froze. Could she hear not one but two voices coming from inside? Two children. Two boys in conversation, laughing and joking. One of them her son, yes… and the other?

She lowered her hand and twisted the door handle.

The scene that confronted her was an unremarkable one, yet not one that gave her any sense of relief—Kelvin sitting cross-legged on the bed with a comic open on his lap, the guy next to him, shoulder pressed against the wallpaper, mask askew on its round football head, arm twisted in a rubbery, inhuman curve. Kelvin looked at her as if interrupted mid-sentence.

“Sorry,” Iris said, feeling foolish. The TV was on downstairs and the other voice must’ve come from that. Mustn’t it? “I… I thought you had a mate in here.”

“I do.” Kelvin smiled.

It took her a moment to realise what he meant. When he grasped the guy’s hollow Christmas-gloved hand in his, a damp chill dispersed in the bowl of her pelvis.

“Come downstairs.” She stiffened, trying not to let the feeling intensify. “I don’t like you spending all this time in your room.”

“I do.”

“Well I don’t. Do as you’re told.” She found a firmness in her voice that didn’t come naturally. “And put your friend out in the shed, please. He doesn’t belong indoors.”

“Who says?”

“I’m saying, and I’m your mam.”

“I don’t have to do what you say.”

“Oh, don’t you?”

“No. And neither does he.”

“I’m not arguing, Kelvin. You can either do it now or you can talk to your father when he gets home. I’m not kidding.” She said nothing more, ignored the fact he threw the comic onto the floor, and went back downstairs to let him stew.

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories