- Home

- Mark Morris (Editor)

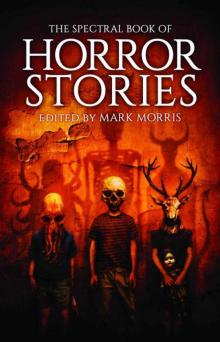

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Page 29

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Read online

Page 29

She sat and watched the BBC news with Kenneth Kendall as her son put the back door on the snib and hauled the guy out into the yard to the garden shed in the corner with the peg holding closed the latch. Feeling sorry for him now, she went to the kitchen, made him a glass of orange squash, brought it in and put it on the table with a couple of chocolate digestives, but when she turned she saw him standing, still clutching the guy to his side.

“He doesn’t like it in there. It’s too dark and smelly. It smells of paint. It’s horrible.”

“I don’t care,” Iris said. “He’ll like it in there when he gets used to it. He wants a home of his own.”

“No he doesn’t. He said he doesn’t. It’s too cold. He likes it in here. In our home.”

“Kelvin, I said no.” She was utterly powerless as he dragged the guy past her and back upstairs. “I said No!” But she knew he wasn’t listening, wasn’t even hearing. She didn’t go up and, for the rest of the evening, he didn’t come down.

Later, while Des was doing his marking in the middle room, she watched Steptoe & Son and couldn’t concentrate at all. Albert had broken Harold’s prize Ming vase and the audience on the laughter track was finding it hilarious, but it was all Iris could do to stop bursting into floods of tears.

#

It was Tuesday morning and she had some thinking to do, not something she was ever told she was good at. She didn’t have a degree like her husband. The most she’d learned in school was how to sit up straight, and couldn’t wait to leave that place, even if it meant working behind the bar in her father’s pub, The Collier’s, till her brother rolled in with a silly sod he’d met on National Service who pulled faces and acted the goat when she played The Blue Danube at the piano. Didn’t think she’d go on and marry him. Not in a million years. Neither did his mother, who didn’t approve and thought he could do better than a publican’s daughter, and made that plain on more than one occasion. She wished she could speak to him now, about her fears, her daft ideas he’d probably call them, but how could she do that when she couldn’t even talk to him about the chemistry of fireworks?

Instead she made herself a pot of tea and gradually let it warm her insides and the mug warm her hands. She wondered what a doctor might say about Kelvin and his new obsession with the object he had created? That there was no harm in it? That it was just like his collecting Mexico ‘70 coins? That it was just a phase he was going through? But what sort of phase, and why? She remembered, herself, as a ten-year-old having a sudden hankering to play with the teddy bear she’d adored when she was two or three, really wanting it back in her life, and asking her mother to find it in one of the tea chests in the attic. Had she wanted it to replace something missing? She couldn’t remember. Did she just want it because it was somebody she loved, and she imagined loved her back?

She knew Des thought she wrapped the boy in cotton wool, that she was too much of a blinking softie half the time. Maybe men in general think a child should be told what’s what. Do this, don’t do that. Maybe it’s about rules for them. Their rules, that is. But what about happiness? Did happiness ever come into it? She just wanted her son to be happy, and he wasn’t. He couldn’t be. Not when his best friend was a…

Then it struck her, what should’ve been blindingly obvious all along.

That if Kelvin had a real, proper friend there was a possibility he wouldn’t need his make-believe one any more.

“Kelvin,” she said at lunch time as he ate his sausages and beans. “Why don’t you ask your friend Gareth to come over for tea tonight?” Kelvin stopped chewing. “I’ll phone his mother and make sure it’s all right with her, but I’m sure it will be. You can show off your guy. I’m sure he’ll be impressed.” She didn’t get an immediate answer, and Kelvin buried himself back in his dinner.

“And he’ll enjoy it too,” he said, looking over at the pile of clothes stitched into a human shape. “He hasn’t got any friends either, see. Just me.”

“Exactly,” she said, wiping the drip of tomato sauce off his chin with her finger.

She phoned Gloria Powell while he ate his thin brick of Walls ice cream, then accompanied him to school, stopping off on the way back at Graigwen Stores to stock up with what she needed for tea. Jaffa cakes seemed a necessity, and she got a tin of salmon for sandwiches (it was a special occasion after all; she felt it was); oh, and some individually wrapped Cadbury’s Swiss rolls, as well as bottles of white pop, Tizer and dandelion and burdock, just in case. It was a hike back home, but she found she had a spring in her step and didn’t stop to catch her breath till she reached Jeff Beech’s sweet shop, lightheaded, round the corner from her house in Highfield Terrace.

As it happened, Gareth said he’d like a cup of tea, please—he always had tea at tea time: didn’t they? Iris said they didn’t, not always. Or rather, she and Kelvin’s dad had tea, but Kelvin didn’t, he preferred squash. It already seemed a difficult conversation and she wondered why she was getting so flustered, given she was talking to an eight-year-old. The way he sniffed suspiciously at the salmon sandwich also didn’t greatly enamour him to her. She said they could go upstairs and play with Kelvin’s Scalextric if they liked, or Monopoly. Gareth said he always beat his sister at Monopoly. Kelvin said he didn’t like Monopoly anyway, he liked draughts best. Gareth sniggered, repeating the word derisively and said his father was teaching him chess. He asked Kelvin what his dad was teaching him.

“Anyway, Gareth,” Iris said. “What are you doing on November the fifth? Going up the quarry to the big bonfire?”

Gareth shook his head. “My dad gets a box of fireworks and lights them in the backyard. I’m allowed to hand him them, but he lights them.”

“Quite right too. Light the blue touchpaper and stand well back!” Iris laughed, hoping the boys might laugh too, but they didn’t see what was so funny. “I hope you keep your cats and dogs indoors.”

“My mam and my sisters have to watch through the window. They always put their fingers in their ears. Dad says this year I can light a rocket.”

Kelvin had left the table and now plonked himself down next to the guy on the settee. Frowning hard, he entwined its arm round his. “He wants to watch TV.”

“What do you want to do, Gareth?”

Gareth shrugged.

“Well, you go and sit down and watch TV with Kelvin, and I’ll get some cake and biscuits. How’s that?”

Out in the kitchen she folded paper serviettes and arranged the mini-rolls on two small plates. A sense of satisfaction sank in as she heard nothing from the other room but the twinkly ‘gallery’ music from Vision On, played when they showed the drawings and paintings sent in by its child viewers. The boys were quiet. They were getting on, thank goodness, she thought. She’d been right. It was working… Then the spell was broken, the apparent calm torn asunder by a lilting, innocuous rhyme.

“Remember, remember, the—”

“No!—”

“Fifth of—”

“Shut up!”

“—vember. Gunpowder, treason and—”

“Don’t! Don’t do that!”

“—reason why gunpowder treason should ever be for—”

“Don’t! DON’T HURT HIM!” This turning into a shriek. From her son.

Iris couldn’t get into the sitting room quick enough. “What the heck is going on in—?”

Three small figures sprawled, entangled on the cushions of the settee, limbs for a moment indistinguishable. Kelvin was wrestling the guy away from Gareth who in turn seemed to be making pincer-like gestures at the effigy’s polo-neck with crab-like hands. Kelvin tugged the guy’s head towards him protectively and flung a foot out at the other boy, aimed at his face. Luckily this was countered by a swing of the arm, while Gareth’s other arm swiped the guy with a karate chop in the middle of the chest, caving in the torso with a massive dent and bending it double. Kelvin emitted an even more ear-piercing shriek.

Iris caught his free hand, “Now! Stop it! Both of yo

u!”

“He was pinching him!”

“I don’t care what he was doing. You don’t kick someone. Is that clear?”

“But he was—”

“I don’t care! Is that clear?”

Kelvin scowled at his mother, eyebrows lowered, eyes black as coal. She was frightened by what she saw there—perhaps because she saw herself, her hatred of herself, or her husband’s— but just as quickly the moment was snapped in half.

“Owww-ah!” This time the cry came from Gareth Powell, who was rolling around, knees in the air, one hand pressed into his armpit, then shot to his feet, tears springing to his eyes as he hopped up and down. “He bit me! The pigging thing bit me!” The boy held out his finger and the scratch across it welled with a ruby pearl of blood. Acting automatically, Iris held it in her hand and the boy continued sobbing pitifully—it made her think of the little baby he once must’ve been rather than the superior little prig he was now. She hastily took out her handkerchief and started dabbing, but it kept on bleeding. Damn, it wasn’t just a scratch, it was a cut. A bloody deep one. How the hell had…?

She wrapped his finger in her hankie as she looked over at Kelvin, whose arms were wrapped round the guy, hugging it, rocking it slightly as if to comfort it after the unprovoked attack it had suffered at the hands of a stranger. Iris instantly saw that the safety pin that held the anorak in place over the guy’s chest was undone.

“It’s all right, love. It’s just a nick. Just a flesh wound, like they say in the pictures, eh? Nothing serious. It was just the safety pin caught you, that’s all, look…”

“It wasn’t!” Gareth bleated, snot dribbling from his nose, his eyes reddening slits. “I didn’t touch the safety pin! Wasn’t anywhere near it! Didn’t do anything!”

“All right, get upstairs you.” Iris pointed Kelvin to the stairs and he shambled away with hunched shoulders, the wobbly-legged torso trailing after him by one inelegant sausage arm, one flaccid glove.

Gareth said he wanted to go home, and kept saying it throughout the process of Iris putting an Elastoplast on his wound—which wasn’t that shocking, certainly not shocking enough for the hysteria it engendered. She then realised that Gareth wanted to go home not because he was hurting or in pain, but because he was terrified. He was terrified of staying there any longer, and the thing he was terrified of was upstairs.

#

Des walked in and asked what was going on. Iris said she was taking Gareth home, she’d explain when she got back, and she did.

“Hell,” he said, swilling a Scotch behind his teeth. He never drank spirits. Never drank at all, really. The bottles only came out at Christmas, and she’d never seen him tight. “This—this, whatever it is—attachment he’s got, don’t you think it’s embarrassing enough without advertising it? Seriously?”

“I just wanted…” She rubbed the back of her neck.

“Well, great. Well done. Tomorrow it’ll be all over the school. You know what children are like. He’ll be a laughing stock. None of the other kids will touch him with a barge pole.”

“It’s a phase,” she said, trying to convince herself.

“What if it isn’t, Iris? What if it doesn’t go away or get put right? What then?” He wanted his wife to answer but she didn’t. Couldn’t. “What do we do? Do we take him to a doctor?”

“No. I don’t know.” She held her head in her hands. “We just have to act like it’s normal.”

“It’s not normal though, is it, eh?” A distant fire engine whined. Bangs and splutters adorned the air, more plentiful now than even the night before. “Is it?”

#

At breakfast they sat in thorny silence over their plates as Kelvin chattered about how much blood was in the average human body, that the heart pumped it round and round, that’s why we had redness in our cheeks, and other organs did other things, like the kidneys that got rid of things the body didn’t need, but sometimes the things the body didn’t need stayed in the body and got worse.

“How did you find out that?” Iris asked wearily. “From school?”

“No,” said Kelvin with a mouthful of Frosties (They’re Grrrrrreat!). “He told me.”

The guy occupied one of the straight-backed dining chairs at the table, semi-deflated and lolling, its mask tilted, giving the illusion it was staring at the bowl of Coco Pops in front of it. Kelvin reached over and lifted a spoonful to its smiling slit of a mouth.

“For God’s sake…” Her husband left his seat.

“Quiet,” Iris said. “He’s only playing.”

“And I’m only on my way to work.” Des struggled into the arms of his gabardine mac. She followed him to the kitchen, stopped him opening the back door. “This has gone beyond a joke,” he whispered, fear and desperation as well as rage in his eyes. “That kid needs to see a bloody psychiatrist.” She let the door open wide for him to go.

The bowl of Coco Pops was empty when she returned.

“Don’t get upset,” Kelvin was saying to the guy, tugging its sleeve. “You’re one of the family. He loves you really. He just doesn’t know how to show it.”

The boy looked round at his mother. His lips twitched, but failed to resolve into a smile.

#

On the way back from shopping that day, Iris chose not to walk her usual route past the police bungalows and up the hill. Instead she decided to go the other way, up Graigwen Place, the way the bus went, then took the shortcut by foot round by the quarry. The bonfire had grown, and she wondered how, since nobody was in evidence. What made a person build a thing like this for enjoyment? Was it just children? Obviously not. Part of a fence had been added, as well as a broken ladder, and even a couple of doors—doors!—and a good number of large branches, of uneven lengths and thicknesses, some as hefty as telegraph poles, propped and criss-crossed, tepee fashion. She stood looking at it when a banger landed near her feet. It cracked, making her jump, then banged again two or three times, flitting around her before phutting out. She called out bitterly, telling someone they were stupid. Nobody replied, and she could hear only an aeroplane crossing the sky. She walked away rapidly. Whatever fool had done it was hiding, or was gone.

#

“God, what’s wrong, love?”

Kelvin stumbled past her, flailing arms, red cheeks wet. His school bag hit the floor. He started to climb the staircase on all fours, then collapsed with his face buried in crossed arms.

“What’s happened?” Iris went and placed the flat of her hand on his back, rubbing it in circles, feeling his tiny chest rising and falling in awful shudders—it almost made her well into tears herself. “Love? Tell me. Please. Tell your mam. She’ll make it better.”

He turned on her, viciously. “How? How will you make it better? You can’t!”

“Well tell me what it is, love, please. I can’t do anything if I don’t know, can I? Come downstairs and I’ll get you a nice glass of—”

“I don’t want a glass of anything!” His voice cracked, throat already raw and swollen. “I just want…” The sentence disintegrated into sobs, and Iris could do nothing but tear off her apron, lie there on the stairs on top of him and wrap her arms around him, tight, whether he wished her to or not, whether he struggled or not, and let him wail until he could speak. His little body shook in the embrace of her. She felt the warmth of him, the salt-streaming helplessness of him and tried to absorb him and rid him of it, but she could not. And the cruelty was he didn’t even want her, and pushed her off him, and clung to the banister rods instead, too much the man, not letting his mother see him cry, poor baby. Not wanting her. But she wanted. She wanted so much.

“They… they said it’s tomorrow…”

“What’s tomorrow, love?”

“Bonfire Night! November the fifth!” He was incensed at her ignorance. “The boys in school said I’ll have to burn him. I won’t have to burn him, will I?”

“What boys?”

“Gareth. Everybody!”

“You d

on’t want to listen to Gareth Powell…”

“It’s true though, isn’t it? The teacher said. We had a whole lesson about it. That’s when they started laughing at me!”

“Oh, sweetheart…” She ruffled his hair and kissed him through his pullover. “It’s November the fifth. It’s okay. It’s what everybody does. It’s a celebration…”

“Why?”

“Guy Fawkes was a man who stored up barrels of gunpowder in the cellars under Parliament and was waiting there to light the fuse, but he got caught.”

“But why do we have to burn him?”

“I don’t know. I suppose we have bonfires and fireworks to give thanks he didn’t succeed. Our politicians weren’t blown sky high—so we burn our own poor old Guy Fawkes instead.”

“Yes, but we don’t have to, do we? Why does he have to die? It’s not fair!”

“It doesn’t matter. It’s only a silly old bunch of clothes, love. He’s not a human being. He’s not alive.”

Kelvin turned and began screaming into her face. “You’re not alive! He is! I know he is—but you’re not! You don’t care about him! You don’t love him! But I do!”

With that he ran up to his bedroom, where she found him, face down in the pillow, next to the guy, which was lying on its back staring up at the ceiling, still bouncing very slightly from the weight that had just landed on the bed. To Iris it looked almost as if its head was moving from side to side. She sat on the bed next to her son and touched his body again. Couldn’t bear not doing.

“Kelvin. Kelvin, love…”

He turned his head the other way, facing the guy and not her.

“We don’t have to go to a bonfire,” she said. “We don’t have to go to a big firework display. Your dad can just light a few—”

“Stop it! Don’t talk about it!”

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories