- Home

- Mark Morris (Editor)

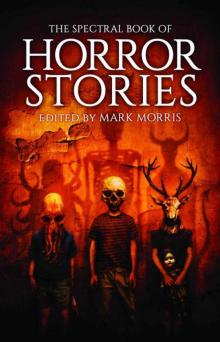

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Page 30

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories Read online

Page 30

“What? Firework night?”

“Shut up! Don’t say those words! You’re upsetting him!” Kelvin threw one arm across the guy’s chest, tugging it closer to him and lowering his voice to a hush. “It’s all right. Don’t worry. I’m here. I know you’re scared but nobody’s going to hurt you. I won’t let them.”

“Kelvin, it’s November the fifth and…”

“Don’t! Don’t mention it again!” He glared at her. “How would you like it? To be stuck on a pile of sticks and set fire to? It’s horrible!” His head spun to the guy. “Nobody’s going to burn you, I promise.”

“Kelv, you have to burn him, lovely…”

“Why? Why should I? I don’t want to. I’m not going to! There’s no law against it. He’s mine! I’m going to keep him, just like he is. You can’t make me!”

A voice said, “Nobody’s going to make you do anything, son.”

Iris turned and saw her husband standing at the bedroom door.

#

She struck a match and lit up, grateful to have the house to herself again. Almost to herself. Herself except for… it.

Des had told Kelvin to get his football togs on, sharpish; they were going to be late for the match if he didn’t get his skates on. His voice had been uncharacteristically mellow, soft—not even rising to accuse his son of having forgotten the extra-curricular game. Iris’ first instinct had been to think something was wrong. She expected Kelvin to resist, say he didn’t want to go, but he didn’t. He sat up, rubbing his eyes with the heels of his hands, probably not wanting his father to see the state he was in. Come on. Shake a leg, buttie. You don’t want to let the rest of the team down. They’re waiting for you. Kelvin had stripped to his underpants. She’d left the room, feeling redundant as Des helped him lace up his heavy, studded boots. Atta boy… Then she’d called out, wishing him good luck, then heard ‘Bye, mam! Though it was not Kelvin who’d called back but her husband. A second later Kelvin’s face appeared round the sitting room door, but he had no need to voice his anxiety. She’d already anticipated it:

“I’ll look after him. You go and enjoy yourself.”

She’d have liked a kiss on the cheek but that hadn’t been forthcoming. She was a bad person now, in his eyes. She couldn’t help that. Just hoped he’d return in a better mood, and that they could have a cwtch watching telly like they used to. Wished that more than anything.

Now, smoking as she bent to poke a lacklustre fire into life, then pulling a guard in front of it, she wondered how much of the conversation upstairs Des had heard. She’d known what he was doing—he was clever, with his degree and everything, after all—distracting the boy with something physical to get his mind away from the damned guy for five minutes. That much was obvious. But what did he think of her? Did he think she was being panicky? Shrill? A bit mad? Had she said the right things? Hell, why was she frightened of what he thought? She wasn’t the problem after all, was she? And when her husband had opened and closed the front door he must’ve let the night air in, because she got that smell of sulphur again, rank and noxious in her throat.

From her chair Iris looked at the ceiling above her, picturing beyond the swirls of Artex her son’s bedroom and its twisted, cuckoo occupant.

I’ll look after him.

She wouldn’t. She wouldn’t go up there. Bugger that. She didn’t want to, and didn’t have to. She’d sit here and read her magazine by the fire and watch Nationwide and whatever else was on until they got home, and then it would be over with. They’d be a family again and she’d make supper on trays, or maybe Dad would get fish and chips from up the Graig, and that would be that.

Which was fine until she needed to go for a wee, and for once she wished she could go outside to the back toilet, but Des had converted it into an extension of the kitchen for the washing machine and tumble drier.

She literally crossed her legs. Then she thought: This is damn silly. I’m not afraid of it. What the bloody hell is it I’ve got to be afraid of? It’s not even made of anything. It’s nothing.

With determination she shot out of her armchair and went upstairs, switching the landing light on and for some reason making her footfalls heavy, as if somebody might be listening, and wanting them to be aware she was coming.

She stiffly walked past her son’s bedroom door to the bathroom at the end of the landing, once inside locking the door after her, even though she was the only one in the house. Sheer habit, she told herself, that was all.

She sat on the toilet seat but nothing came. Her bladder was empty. She felt desperately weary again, drained from seeing Kelvin so upset earlier, she supposed. As his mother she couldn’t stop herself being affected by what affected him. It was part of what being a mother was. A kind of symbiosis you were never free of. If they suffered, you suffered. There was no getting away from it.

She stood up and pulled the chain even though she hadn’t gone, staring at the swirling water and remembering the terrible day she’d seen blood staining the white of the pan.

She heard footsteps on the stairs. Light. Far too light for a grown man. More like a pet, but they had no pets. And not walking so much as scuttling.

“Kelvin?”

She zipped up her slacks and opened the bathroom door.

The landing was empty. Kelvin’s bedroom door shut. Of course it was.

She was being stupid. It was probably the kids next door. The terrible twins. They were always running up and down stairs, causing a riot. That was it. Yes. Definitely. What else?

She went back, washed her hands at the sink with the brick of Imperial Leather, dried them with the towel, then tugged the ring-pull to switch off the bathroom light.

Downstairs she walked into the sitting room and saw the guy slumped on the settee in the glow of the TV set, for all the world as if watching it, stunted legs sticking out with socks dangling at the end of them, fat arms hanging limp at its sides, gloves bunched up, non-fingers at inconceivable angles.

Iris’s hand clamped over her mouth.

Her first thought was that she had mis-remembered earlier, that was it, that must be it, and that Kelvin must’ve brought down the guy before he’d left for the match with his father—but she’d been sitting in the room only minutes earlier and it wasn’t there! Surely that was true—wasn’t it?

She laughed. She didn’t decide to, she just did. It just began to happen. And she didn’t even know what she was laughing at, but she couldn’t stop.

Minutes later she ran out of breath, and went to the front room and raided the drinks on the hostess trolley and poured herself a gin and tonic, and when she’d drank it, poured a second one.

The guy was still there when she returned. It hadn’t moved. That was one thing, at least—it hadn’t moved. She wondered if she sat there long enough it would, while she was looking straight at it. But no, of course not—it was too clever for that. Cleverer than her, anyway. She knew where it got that from, its brains…

She switched the TV off, because she hadn’t switched it on. She was positive she hadn’t. And she sat cross-legged on the floor with her back to the screen, because that’s where the guy’s face was pointing.

“You’re treating this like your house,” she said to it bluntly, pleased that she was managing to disguise her emotions. “Well it isn’t. It never was and it never will be.” She sipped her drink and tried to discern what, in its cheap plastic smile, it was thinking. Or was it just mocking her? Mocking all of them? “What do you want with us?” Her eyes narrowed. “What do you want with him?”

Even as she said it, she knew the guy, in his cunning, would not reply.

#

When the wanderers returned she was in her bedroom, curled up but not asleep, as far away from the guy as possible. Coming down when she heard the door slam, she asked how the team had done, whether he’d scored, but nobody told her. She crossed Kelvin on the stairs, his white shorts muddied and his knees scuffed. Down in the sitting room she found Des lifting the guy

by one shoulder. “I better take this upstairs. Or he’ll go nuts.” Iris tightened the belt of her dressing gown as he—they—passed.

By the time Kelvin had had his bath, Tom and Jerry had finished and Star Trek was on, but the boy didn’t come down to watch it, though he never missed an episode. He loved it. But tonight he wanted to be with the guy, Des reported. Because the thing had missed him, Des said.

“Didn’t you tell him he had to?”

“You’re forgetting who the boss is in this house.”

“Who?”

“Well it’s not bloody me.”

At nine o’clock, just as Special Branch starring that actor with the thick lips started, Des took up a hot water bottle and put Kelvin to bed because Iris said she was still in the doghouse for some unknown reason. When he returned back down he was carrying the guy like a sack from its scrawny neck.

“I know. I know. You go and talk to him if you want to. He said it wants to sit with us and get to know us, apparently, so we’ll ‘grow to love’ it.”

“I don’t want to love it,” Iris said through gritted teeth. She didn’t even want to look at it, either.

“That’s his… logic, I don’t know. I didn’t know what to bloody say.”

“You could’ve said ‘Go to sleep.’ And don’t put it on my nice clean… Christ, put it over there.” She pointed to one of the dining chairs over by the closed curtains, between the phone table and the TV set. Blowing air unhappily, he dumped it there, where it hung, boneless, baby mask snug in the receptacle of its hood.

Sniffing at his sleeves with repugnance, Des sank into the armchair at an angle to his wife’s, also facing Special Branch. “I can smell it on my clothes…” Soon it was clear to both of them that neither were paying a great deal of attention to what the programme was about, though their eyes were fixed on it.

“Today… I was in the bathroom…” Iris shuddered, faltering. “Des?”

“What? I’m listening.”

She shook her head, deciding she didn’t want to go into details. “I… I just don’t like having it in the house. I hate it.”

Des grunted. “And I don’t?”

“But to him it’s like… I don’t know…”

“Probably full of maggots from that pushchair, for a start… Goodness knows what diseases… Spreading its germs…” He plucked the Express from the foot stool and opened it wide, arms stretched.

“Some sort of a… friend… a…” Again, she floundered.

“Stinking out the house…”

“Des, I can’t bear it…”

“You don’t have to bear it,” he said, eyes scanning the sports results. “Not for much longer. Roll on tomorrow and we’ll be shot of the thing.”

“Don’t say that.” Iris was aghast. “Don’t even think that, for God’s sake! We can’t. He loves it. We can’t be that cruel.”

“We have to. For his own good. We have no choice.”

“You said nobody was going to make him do anything. You said that to him a couple of hours ago.”

“I know. I lied.”

“He won’t let you. You know that. He won’t let him go.”

“He’ll have to,” Des said. “He’s got to grow up.”

“Why?”

“Because we all have to.”

Iris started to cry, and perhaps she wanted him to come over and put his arms round her and hold her tight, or perhaps she wanted him to fall to his knees and cup her hands in his, or wipe her tears away with his thumbs in a gentle and caring gesture. But what happened was, he sighed and folded up his newspaper, dropped it into his lap and turned to her with tight lips, dry eyes and an expression of intense irritation.

“What can I do? What do you want me to do? Tell me.” When she didn’t, he said, “Breathe. You know what the doctor said. Breathe.” And she wished and prayed that his eyes weren’t so dry and his lips weren’t so tight and he would just tell her everything would be all right, but she knew he couldn’t. He got up and turned down the volume on the telly, but that only made the chemistry of fireworks louder. “Tell me what you’re thinking.”

“You know…” she began. “You know how, when he was younger, Kelvin would have a nosebleed every so often, and it was weird—he didn’t know it, but we did. It would always be at my time of the month. Like clockwork. I’d start to bleed, and the next thing, he’d be saying…”

“Iris…”

“No, like he was in tune with me. Like he was part of me, still. And if he’s part of me, does he know what…”

“Stop.”

“It was my body. I mean, did he feel…”

“Stop it!”

Now Des was on his knees in front of her, but not kissing her and not holding her, but gripping her wrists. She feared he would shake her. Strike her, even. But his grip became feeble, impotence turning to sudden alarm in his eyes.

“Why the hell are we whispering?” But they both knew the reason.

The reason was behind him, slumped half-on, half-off the dining chair like the imitation of a husk of a corpse at a wake, long arm dangling, chin sunk into the crater of its chest.

#

Remember, remember… Dread wasn’t a word she thought about very often but dread was the only word that would do. As soon as she woke she couldn’t wait for the day to be over. The fifth of November… The old feelings flooded back. She couldn’t stop them. She didn’t dress, and asked Des to make the boy his breakfast, please. Gunpowder, treason and plot… Alone in the double bed, she turned over into the pillow but was unable to drift back to sleep. She had a splitting headache pounding against her skull, a real humdinger. Not even a shower and two aspirins from the medicine cabinet did anything to shift it. I see no reason why gunpowder treason…

Hearing Des leave in the car, she shambled downstairs in her dressing gown and slippers to make a cup of tea. Maybe that would do the trick. Kelvin sat on the settee looking pale. She looked at her watch. She’d expected him to be halfway to school by now. He gave a few unconvincing little coughs into his fist.

“I don’t feel well.”

“You’re going to school. I don’t care what day it is.” She tugged open the curtains, tied them back with the cords. The sky was like dirty dishwater.

“I’ve got a temperature.”

“You think I don’t know what you’re playing at, young man? That’s enough of that malarkey.” She held out his school bag to him.

“I have to stay here with him. I have to protect him.”

“Please, love. Not now. You’re being silly.” She rubbed her forehead. It was as sore and agonising as if she’d prodded a wound.

“I’m not being silly! People want to hurt him. People want to burn him!”

“Nobody’s going to do anything. Nobody’s going to get in here, are they? I’m here.”

“But I don’t want to leave him all alone—because he’s scared, really scared!” Now her son’s voice was going through her and she couldn’t stand it. She certainly wasn’t up to a full-volume row with a forceful and stubborn eight-year-old.

She crouched down, took his hand in hers and kissed it. “Sweetheart, I know he’s been a really good friend, but…”

“But he’s not a friend. He’s not just a friend. You know that!”

Her heart flipped. Her throat tightened. What did he mean? You know that?

“All right.” She let go of his soft flesh and stood up quickly. “Just this once, all right? You haven’t got me round your little finger. Don’t think that for one minute. I’ll phone the school and say you’re feeling poorly.” No sooner were the words out than he got up and threw his arms round her hips, pressing his cheek to her tummy. She held in her breath, arms aloft, until he let go.

Moments later she could hear his voice as he reached his bedroom: “She said you can stay! She said you can stay forever and ever!” She saw herself shudder in the mirror over the mantelpiece.

Blap-ap-ap!

Rockets were going up early.

She couldn’t tell where, probably over Maes-y-Coed. She was protected by the windows from the occasional and unpredictable bursts—going off like some small-scale civil war—as she rang the secretary in the primary school office, saying her son had a cold and wouldn’t be in today. When the secretary sounded sympathetic and said she hoped Kelvin felt better soon, Iris felt guilty and hung up abruptly, then regretted it. Goodness knows what impression it gave, but she felt under a lot of strain and she didn’t want long conversations with people. Not today, of all days. Even that simple task had been an enormous strain—okay, it shouldn’t have been, but it was.

Not long afterwards, Des rang, which he never did. Between lessons.

“How did he get off?”

Iris thought of lying, but didn’t have the strength. “He wouldn’t go.” Des didn’t sound as if this was totally unexpected, but it’s hard to tell on the telephone exactly what somebody is thinking. Perhaps he was thinking it was her fault—being soft again. “It’s only one day,” she said. “What does it matter?”

“I’ll see you at five-ish,” he said. “I’ll come straight home.”

“You don’t need to.”

“I do.”

#

Mid-morning she wanted to get a tin of Heinz cream of tomato soup for Kelvin’s dinner. But the truth was she wanted to get out of the house. She was rattling in it and it was jangling her nerves. As she walked downhill to the shop in the burnt, already pungent, nitrogenous air, she wondered how the bonfire up the quarry was doing, whether it had enlarged, swelled, whether it was gathering bulk even now for the festivities that would kick off come nightfall when grown-ups and their offspring alike gathered to celebrate. Celebrate what? Celebrate death. She wished the air was clean and fresh and reviving but it wasn’t.

“Penny for the guy?”

Two munchkin sentinels stood outside the Spar. One wore a mask of Frankenstein’s monster in lurid green and the other, a girl in pigtails, the more traditional Guy Fawkes. Their construction, which sported a ‘Dai’ cap and cricket pullover, wasn’t nearly as impressive as her son’s—its face merely a child’s crayon drawing wrapped onto a cardboard box with Sellotape.

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories

The Spectral Book of Horror Stories